Interpreting Beethoven: Broken Metronome

When talking about Beethoven you can’t ignore the fact that his metronome markings can be extremely high, and sometimes it is physically impossible to play as fast as he indicated. This has led to a lot of theories and myths to try and explain why Beethovens metronome markings are so high, so in this article I wanted to share my thoughts on the most known theory, the Broken Metronome theory.

I know there is a lot of research out there on Beethoven and his metronome markings, and he didn’t even put metronome markings on any of his cello sonatas, but I wanted to share my thoughts around this theory. In the next article I will show you some other theories and evidence I have found, and later I will discuss how us performers can use this knowledge when choosing tempi for other pieces without metronome markings.

The Broken Metronome Theory:

This theory states that Beethovens metronome was broken and ticked slower than indicated, which means all his metronome markings indicate a faster tempi than he actually wanted. This is a theory most musicians believe, and I have to admit that I also thought this for many years. It makes sense when you see how high his metronome markings are, and would explain a lot, but the fact is that this theory can not be proven nor disproven.

The metronome that we know belonged to Beethoven is actually broken today, its missing the weights on the bottom, and without those weights we can’t know if they were the presise weight they needed to be for the metronome to be correct. They might have been the wrong weight and therefore this theory might be right, as most musicians believe, but here is a few facts that might make you think twice about that.

«Either the metronome was broken, or he shows an incomprehensible lack of judgement in deciding the speed»

This is a quote by the famous pianist Leopold Godowski from the preface to his 1915-edition of Schumanns Kinderszenen. I’ve actually heard musicians say similar things about Beethoven, Schumann, Czerny, Chopin and Hummels. Everyones metronome was broken, and in exactly the same way! And guess what, these great musicians didn’t even notice their metronome was broken, and none of their colleagues or friends noticed their metronome was broken. Which means a genius like Beethoven didn’t notice that 60 on his metronome was a completely different tempo than the second hand on his clock?

I find that very hard to believe, so I would say that this theory is just a solution to try and justify why we as modern musicians ignore the metronome markings, and it’s much easier to say Beethovens metronome was broken than to admit we don’t understand what he meant with such tempi. But are you still not convinced?

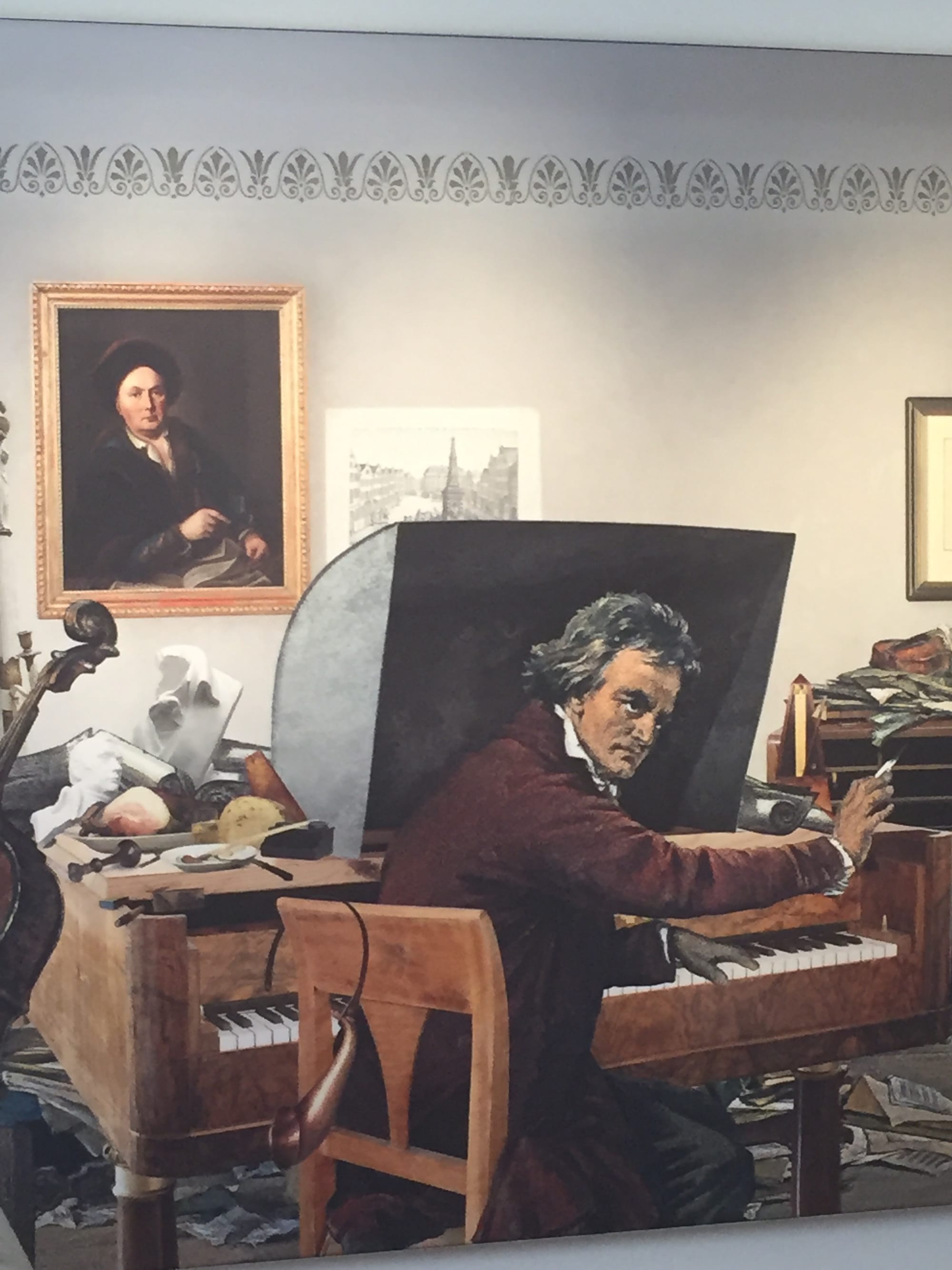

This might just seem like a picture of Beethoven with a weird piano, but this is in fact a quite interesting picture that tells us a lot when discussing the broken metronome theory. When Beethoven started to loose his hearing he had this piano altered in order to hear it better, so it was cut open and the metal plates were put there to send as much sound as possible straight into his face. You can also see one of his «ear trumpets» hanging on his chair, which was a kind of hearing aid he used, and to his right you can actually see his metronome. Guess who made both the piano invention, ear trumpet and the metronome?

Johann Nepomuk Mälzel.

An inventor and friend of Beethoven, famous for also inventing the metronome. I know its debated if he actually invented it or just stole Dietrich Winkel’s invention and patented it, but he is known as the inventor of the metronome. So with the broken metronome theory there isn't only Beethoven who didn’t notice it being broken, but also the inventor himself who clearly was around a lot when making these hearing aids.

So I’m pretty convinced Beethovens metronome was not broken, but if anyone disagrees I’m very interested to hear why, so please comment below if you have anything to add to the discussion, want to share your opinions or have any questions to me.

And at the bottom of this page you can even subscribe and get an email when the next article is published!

Thank you for reading,

Markus Eriksen